The Adults Young People Need: What True Mentoring Looks Like

Key Idea

True mentoring isn’t about leading, directing, or shaping a young person’s choices. It’s about being a steady, respectful presence who models curiosity, vulnerability, and self-directed learning. When adults show up without taking over, young people develop confidence, voice, resilience, and a healthier understanding of adult–child relationships.

Why Mentor Roles Matter in Self-Directed Education

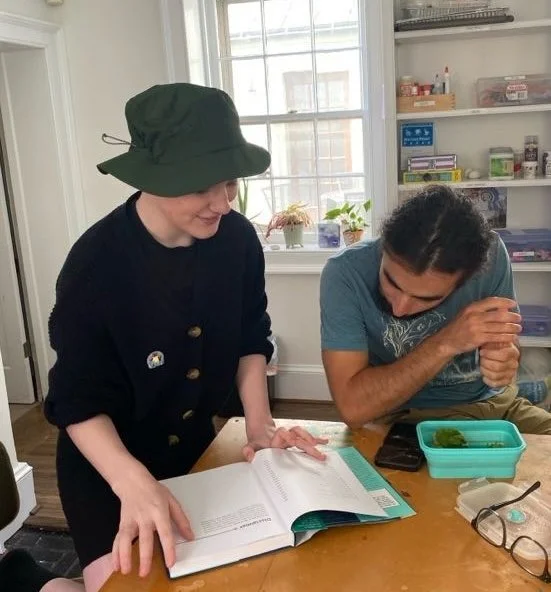

At Embark Center—and in any environment centered on young people’s autonomy—mentors are not instructors, supervisors, or authority figures. They’re support staff, intentionally positioned outside the traditional adult-in-charge dynamic.

Children and teens who pursue self-directed education aren’t learning subjects. They’re learning how to navigate the world, advocate for themselves, identify their interests, tolerate uncertainty, access resources, and collaborate with others. For this to feel real and trustworthy, they need adults who don’t dominate the process.

Mentors create that environment by offering connection without control.

Support Without Steering

Traditional schooling positions adults as leaders who set expectations, monitor progress, and correct mistakes. In contrast, truly supportive environments ask something more nuanced: adults who are present, curious, and supportive—without taking over.

Effective mentors:

Offer tools, not routes

Ask questions, don’t deliver conclusions

Share reflections, not directives

Stay available without hovering

Support the learner’s goals, not the adult’s preferences

Bring steady presence rather than expertise

Young people quickly sense when an adult’s “help” is really an attempt to shape the outcome. True mentoring is an act of humility—showing up without needing to be the expert, without needing to be right, and without assuming you know what’s best.

It’s less about having answers and more about creating the conditions where their answers can emerge.

Letting Kids Learn Through Their Choices

One of the greatest challenges for any caring adult is resisting the instinct to protect kids from struggle. Mistakes aren’t just academic. They’re human. They show up in every corner of a young person’s life.

Sometimes kids:

Take on a project then abandon it

Trust someone who doesn’t treat them well

Misread a social cue or react impulsively

Get swept up in group dynamics they later regret

Overcommit because they want to make everyone happy

Try something before they’re ready

Avoid a conversation that really needs to happen

Follow an idea that ends up going nowhere

Shut down when they feel overwhelmed

Handle a conflict clumsily

Misjudge how long something will take

None of these moments are failures. They’re real-life learning. They’re how young people build emotional intelligence, social awareness, resilience, and self-understanding.

When adults rush to prevent, correct, or rescue, kids may feel safer in the moment—but they lose the opportunity to:

Experience the outcomes that lead to deeper reflection

Read situations more effectively

Repair relationships

Practice boundaries

Build confidence in their own judgment

Strengthen their internal compass

A mentor’s role isn’t to eliminate difficulty. It’s to stay close enough to help kids make sense of their experiences, without taking those experiences away from them.

Mentors as Models of Self-Directed Learning

One of the most powerful—and often overlooked—parts of mentoring is that mentors model exactly what we want young people to learn: how to navigate life without pretending to be perfect.

In many traditional adult–child dynamics, adults feel pressure to:

Appear competent at all times

Have quick answers

Hide uncertainty

Not make mistakes

Move past errors without acknowledging them

Kids notice this. It teaches them that adulthood is about performing competence rather than embracing growth.

But mentors in self-directed environments show something entirely different.

They show that:

It’s okay not to know

It’s healthy to ask questions

Curiosity doesn’t end at adulthood

Learning is lifelong

Mistakes are normal and repair is possible

Apologizing is a strength

Changing your mind is allowed

Admitting uncertainty builds trust

When a mentor says, “I’m not sure—let’s figure it out,” they’re modeling self-directed learning.

When a mentor says, “I handled that poorly, and I’m sorry,” they’re modeling repair.

When a mentor says, “That didn’t go how I hoped,” they’re modeling reflection.

These behaviors teach kids:

Adults are learners too

Wisdom has nothing to do with perfection

Being human is more valuable than being right

Relationships can be honest, mutual, and respectful

Mentors don’t model authority.

They model humanity.

How This Shapes Kids’ View of Adults and Themselves

When kids regularly interact with adults who respect their autonomy, something powerful happens:

1. They stop assuming adults are judges.

Adults become collaborators, sounding boards, and resources—not people to impress or appease.

2. They develop their own voice.

Not the voice that keeps adults happy, not the voice trained to anticipate expectations—their voice.

3. They build an internal compass.

Because decisions weren’t made for them, they learn to make decisions for themselves—and adjust when needed.

4. They approach adults with confidence.

They don’t tiptoe around authority. They know adults can handle honesty.

5. They understand consent and boundaries.

Respectful mentoring teaches them that good relationships—at any age—are not coercive.

This is the foundation of empowered adulthood.

At Embark, Mentors Are Not Leaders—They’re Partners in Growth

Embark mentors provide structure without rigidity, support without expectation, and guidance without control. Their job is to create a relationship where young people feel:

Safe

Respected

Heard

Free to explore

Free to fail

Free to choose

Free to change direction

This isn’t the absence of guidance. It’s the presence of trust.

And trust is the soil where real learning grows.